James Bond’s Cold War: the geopolitics of ambiguity

A spectre haunts James Bond — the SPECTRE of Bond’s role in the Cold War.

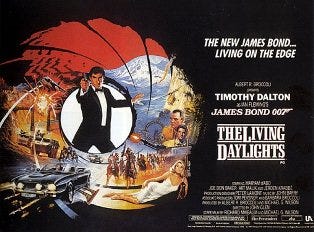

Theatrical release poster by Brian Bysouth

A reposting of a Blog written for the former Geopolitics and Security site at Royal Holloway, University of London in 2019. now no longer accessible.

James Bond’s Cold War: the geopolitics of ambiguity

M. D. Brown

A spectre haunts James Bond — the SPECTRE of Bond’s role in the Cold War.

Let me start by apologising for inventing such an awful pun, but SPECTRE’s (SPecial Executive for Counterintelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, and Extortion) role in the James Bond franchise strikes me as being indicative of its ambiguous relationship with the geopolitical ‘realities’ of the Cold War. Try as I might I haven’t been able to find any convincing evidence Ian Fleming and Kevin McClory had the Communist Manifesto in mind when they ‘jointly’ invented SPECTRE in 1959 – the exact manner of its creation was subsumed into long running legal disputes, finally resolved in 2013 – but the ambiguity of the analogy seems to fit.

As an international historian and an enthusiastic student of all things ‘Bondian’ I find the question fascinating. To me, Bond’s Cold War looks decidedly odd because across the official canon of books and films produced between 1953 and 1989 the West’s communist adversaries are usually kept at arm’s length or are replaced by SPECTRE. (Through the crude Eastern European stereotypes remain firmly in place.) A dislocation that’s even more apparent when you compare it to the worlds inhabited by say, John Le Carré’s or Helen MacInnes’s creations.

It is not that the Cold War was unrepresented: the space race, nuclear weapons, international narco-trafficking, ecological concerns and inevitable shots of a snow-encrusted Kremlin appear repeatedly and firmly locate the series in a recognisable historical period. Rather it’s the ambiguity of the representations of the communist adversary, the considered and deliberate dissociating of the Bond series from the geopolitical and geographical actualities which are noteworthy. Note the absence of references to the conflicts in Korea, in Vietnam, The Congo or Nicaragua, to decolonisation, to nationalism in the Middle East or life in the Soviet Bloc. Huge, significant swathes of the global Cold War are simply missing from the series.

I should admit most of what I have argued above is undermined by a reading of the continuation novels, from Kingsley Amis’s Colonel Sun (1968) through the John Garner and Raymond Benson eras up to Anthony Horowitz’s Forever and a Day (2018). The most recent tranche (published post-2009) are now busily re-imagining the Cold War afresh, incorporating many of the omissions listed above.

As a result, the core ambiguity of Bond’s Cold War is both fascinating and frustrating. I won’t pretend this is an especially novel argument, although I will argue it should be explored further: especially since tales of fictional espionage are now acknowledged as being one of the defining characteristics of Cold War culture and might have played a crucial role in how the stand-off ended. To paraphrase the preeminent Bondologist, James Chapman, we should take Bond’s Cold War seriously.

The point is it’s not really ‘The Cold War’ we perceive in the Bond franchise, it’s a distorted Bondian refraction, and we should be cautious not to conflate the two. Key geopolitical events undoubtedly exerted an influence, yet equally important were production issues, questions of copyright and occasional dumb luck.

Not convinced? Well, nothing exemplifies these dynamics more clearly than the way in which the order of Fleming’s novels was rearranged when it came to actually making the films. Producers Cubby Broccoli and Harry S. Saltzman didn’t start off tackling Dr No because of events in Cuba, they did so because they didn’t then own the rights to Casino Royale and the script for Thunderball was stuck in a legal limbo.

Nor was the distancing of the Cold War in the franchise accidental, rather it was a commercial imperative. Explicit references to the conflict came to be regarded by Fleming, Broccoli and Saltzman as being potentially unprofitable.

As Fleming explained to Playboy (1964), “I thought, well, it’s no good going on if we’re going to make friends with the Russians… So I invented SPECTRE as an international crime organisation … a much more elastic fictional device...” (I find it difficult here to ignore the sheer bizarreness of Fleming’s statement. Remember, he is claiming that he considered an outbreak of détente imminent around 1958-9—and this was a man long responsible for The Sunday Times’ network of 88 foreign correspondents. But anyway, moving swiftly on.) As Broccoli later put it in his autobiography, “We decided to steer 007 and the scripts clear of politics. Bond would have no identifiable political affiliation.” Given Bond’s long-running success this seems to have been a very savvy move indeed.

Yet again, that said, explicitly political films like Dr Strangelove, Red Dawn and Rambo II plus a whole slew of communist-produced espionage thrillers did manage to be popular while actively embracing politics. As I said, fascinating and frustrating.

I would argue the Bond franchise wasn’t simply about responding to the geopolitical environment, it was equally (if not primarily) about generating profit. Fleming was quite explicit about this in his 1962 article How to Write a Thriller. A perfectly reasonable approach, but it does significantly complicate any suggestion Bond was a component in the west’s Kulturkampf. Not least as Broccoli was invited to Moscow in April 1975 to discuss co-producing films with the USSR’s MOSFILM, and later to Beijing.

At this stage, some readers might be wondering what I am babbling on about and if I’ve ever read or seen From Russia, with Love with its stereotypes of Eastern Europeans; had ever noticed the character of KGB General A. Gogal, played by Walter Gotell; was aware Octopussy (1983) was partly set in East Berlin (Roger Moore being the first screen Bond to cross the Iron Curtain), or realised Timothy Dalton’s Bond visited Czechoslovakia and fought the Soviets in Afghanistan in the Living Daylights (1987). Well yes, I know all that, as well as the fact the franchises’ approach to the conflict underwent a wholesale reappraisal with Goldeneye in 1992.

But Bond’s engagements with the Cold War prior to 1989 are at best fleeting, sporadic and profoundly stereotypical, as Umberto Eco and Katerina Lawless have shown. While the Soviets are often the sponsors or beneficiaries of Bond’s adversaries’ plans, they rarely appear in print: a SMERSH [Soviet counterintelligence] assassin saves Bond from Le Chiffre in Casino Royale (1953); Bond admits to having been briefly posted to Moscow and Soviet submarines surface off Dover in Moonraker (1955); Soviet agents are on the loose around Paris in A View to a Kill (1960); From Russia, with Love opens in Moscow as SMERSH plans its revenge on Bond, but the main action unfolds in Istanbul; he engages in a sniper dual across the newly erected Berlin Wall in The Living Daylights (1962); finally, Bond is captured and brainwashed by the Soviets to assassinate ‘M’ in The Man with the Golden Gun (1965), before recovering in time to tussle with KGB agents and Rastafarians in Jamaica.

In the films, the Soviets are usually replaced by SPECTRE, or they’re facing the same threats as the west and are allied with Bond. When Soviet agents do appear as adversaries they’ve usually gone rogue. Yes, there are occasional scenes set in Bratislava, Berlin and Moscow, and, yes, the Cold War lurks in the background, but unless I’ve missed something obvious that seems to be about it.

The Bond canon has much to tell us about Anglo-American relations, Britain’s decline, changing gender roles, global tourism and burgeoning consumerism, but far less about those ideologies and powers which dominated nearly half the planet. We know from his biographers that Fleming visited Moscow in 1933 and 1939 and learned some Russian. But according to research by Jeremey Duns his understanding of SMERSH, and the Soviet Bloc more generally seems to have been largely reliant on the memoirs of one defector, and questionable reports from the journalist Antony Terry, who took him to East Berlin.

On which note, let me try and conclude this blog with a concrete geographical example of the ambiguity of Bond’s Cold War.

Duns makes a convincing argument for The Living Daylights (1962) being the most authentic of all Bond’s Cold War adventures. It was originally a short story and subsequently incorporated into the Dalton era re-boot of the franchise in 1987. In the story, Bond is tasked to assist a British agent escape from East Berlin, and, armed with a sniper rifle, to thwart the KGB assassin trying to kill him. He’s weary and unenthusiastic about the mission, perhaps reminded of his own killing of a Japanese cypher clerk in New York at the beginning of his ‘00’ career. At the denouement, the assassin is revealed as a woman cellist and Bond shoots to wound, not to kill, as a result, he expects to be summarily sacked from the service.

Twenty-five years later the story was resurrected for Dalton’s first tenure as Bond, the location having been shifted to Bratislava in Czechoslovakia, and the escape to Vienna. The latter location allowing for plenty of gratuitous visual references to The Third Man (1947). The escapee is now a defecting KGB colonel, the sniper is his mistress and a patsy. As the story unfolds the colonel is exposed as a crude fraud, running heroin out of Afghanistan to fund arms deals. There are no ideological motivations here, merely the pursuit of gross profit.

Bond returns to Bratislava in his Aston Martin to rescue the cellist and an exciting run across the snowy mountains to the border ensues. A chase begins, lasers are fired, police cars explode, the Aston is destroyed, and they finally swoosh downhill to Austria and freedom-riding inside the cello case.

But…and it’s a big but—the route between Bratislava and Vienna is as flat as a pancake, there’s not a bump in the road. I know, I’ve travelled it. During the Austrian-Hungarian Empire there was even a tram running between the two cities…In a series where the Cold War was smoothed over to the point of indiscernibility, the dictates of cinematic suspense seemingly required the raising of artificial mountains.

All of this probably raises far more questions of than I’ve answered. Fortunately, Bond’s Cold War will be explored further at an event to be held at Tallinn University this summer along with my colleagues Dr Muriel Blaive and Dr Ronald J. Granieri.