I liked Riga.

We recently spent a few days there on a ‘city break’ and I was smitten. Perhaps we were lucky: the weather was great, stayed in a nice central location, treated ourselves to some good meals, and strolled around the museums, parks and sights. My partner and I have been trying to visit the city together for ages, but we’ve never managed it. I am glad we finally did. It wasn’t all smooth sailing but it all worked out in the end.

A few things stood out: above all else the sheer beauty, wealth and range of the architecture (I am a sucker for Art Nouveau so…), the conviviality of the inhabitants and the relaxed pace of the place. Of course, such positive impressions might not be shared by all of Riga’s inhabitants or by more knowledgeable visitors, but as tourists, we couldn’t have asked for more. It’s also pleasant — and rare — to be immediately and utterly taken with a new location, to know it’s somewhere you want to return to.

I am more familiar with Tallinn than with Riga, and the latter is a profoundly different place, obviously enough you might reply, but there’s a cosmopolitan confidence to the city I wasn’t expecting. Tallinn doesn’t possess it, nor does Helsinki: Leningrad did, but that was another place and another time. The population seems comfortable with its urban milieu in ways I’ve not noted in Tallinn…well, take that sanctimonious claptrap with a few fistfuls of salt but that's the impression I came away with. As a Londoner, it’s an attitude I take seriously.1

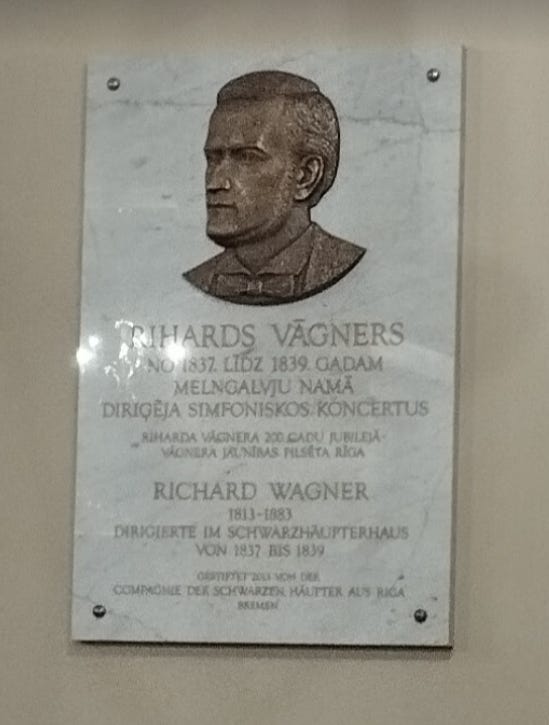

Riga is a grand city that (just about) combines its Thirteen-century Hanseatic roots, with its rapid late Nineteenth-century expansion of boulevards and parks, a traumatic Soviet inheritance and a post-liberation grandeur. Notable are the ziggurat-like new national library along the river, the old Zeppelin sheds that are now a thriving market, and the lovingly restored House of the Blackheads. This is no mean feat to pull off, given Teutonic influences, Russian imperialism, national revivalism, Soviet occupation and a long fight to reclaim independence, which all vie for attention, cheek by jowl, in the Town Hall Square. No, the positioning is not entirely comfortable, but it sort of works: Teutonic bürghers, Latvian riflemen, and anti-communist partisans uneasily co-exist…although I’m not quite sure where Richard Wagner fits in…

C19th urbanisation

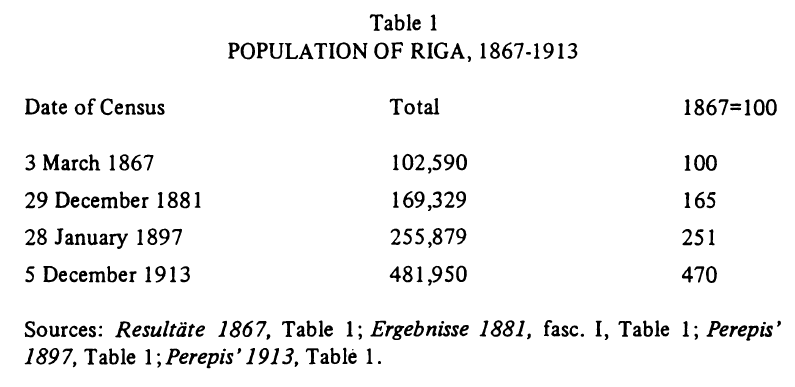

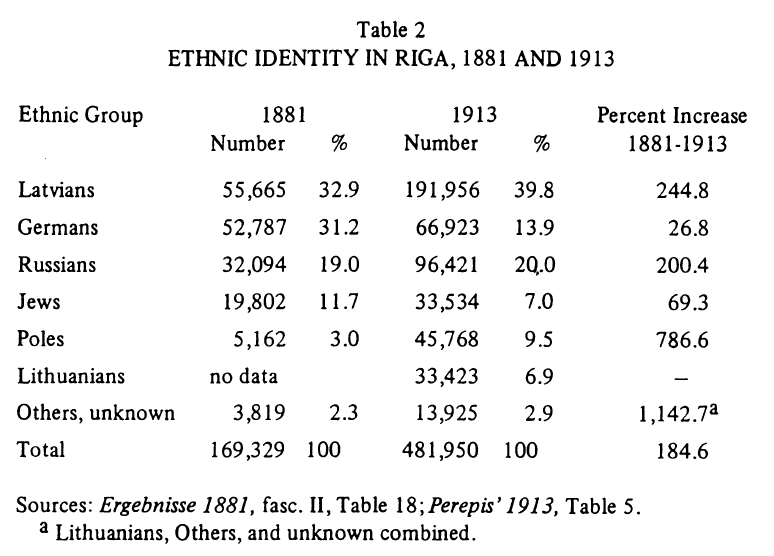

I’ve come away from Riga a tad obsessed about its rapid urbanisation. I had thought Latvia’s wealth was generated during the inter-war era, although some reading has disabused me of this idea.2 I now know Riga’s growth occurred during the latter years of the Russian Empire, becoming the third-largest industrial centre in the country. My ignorance is neither here nor there, but this rapid, industrially-driven growth seems to have been responsible for imparting some swagger to its inhabitants.

Both taken from Corrsin, ‘THE CHANGING COMPOSITION OF THE CITY OF RIGA, 1867-1913.’

A soupçon of sophomoric sociology leads me to posit such urban confidence must be due to the development of authentic, organic proletariat and bourgeoise classes, although, of course, it might equally just be something in the local water. The city’s rapid expansion doubtless hides a whole mess of issues and political and ethnolinguistic conflicts I barely grasp in my ignorance.3 Nevertheless, there’s nothing provincial about Riga, it feels echt.

Art Nouveau

The most fascinating outcome of these developments is Riga’s impressive Art Nouveau legacy. I knew about it but was taken aback by its extent. I had imagined a few streets at most, but large swathes of the city are full of ornate blocks that rival the streets of Brussels or Vienna. It also, and I’ll tread carefully here, lends the city an air of being further west than it is…I don’t mean in terms of civilisation but esthetically. The Paris of the East is a hackneyed phrase and has a fair few claimants, but as titles go it’s not a bad one to get tarred with.

I could write thousands of words and post oodles of pictures on this subject, but three items caught my attention in Riga’s excellent Art Nouveau Centre and its restored flat (I would strongly urge you to visit if you’re passing by): a coffee grinder, a stove and a toilet.

The coffee grinder was a delight, especially in comparison to the capsule coffee maker which is de rigour in all Airbnbs these days — a machine I had used to caffeinate myself that morning. I couldn’t help comparing the two, and which was superior. I think we all know the answer. There was a samovar in the kitchen too, and I don’t recall seeing one of those in the Horta Museum in Brussels. The stove caught my attention as my grandmother had something very similar in her flat, complete with the same sensible metal base plate. Finally, a British contribution to Latvian Art Nouveau interiors: the khazi, or rather The Incomparable Closet. I've no idea how it got there but it’s surely symbolic of Riga’s burgeoning cosmopolitism.

Yet one issue remained a mystery to me, why Riga’s merchants, industrialists and artists embraced the Art Nouveau so enthusiastically? So far as I could tell there was no coherent explanation on offer in the museum. I’m glad they did, but as to why they did I’m none the wiser. Their enthusiasm doesn’t seem to have travelled along the Gulf of Riga to Estonia. Pärnu’s Villa Ammende is a notable exception, but it’s one of the few.

Sporadic restoration

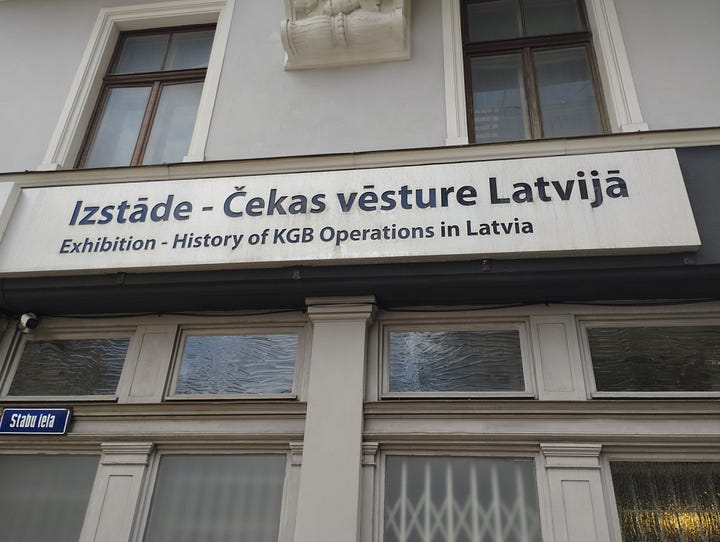

Many, although not all, of Riga’s Art Nouveau buildings have been lovingly restored. Other parts of the city however remain shabbier. The outskirts we arrived through by coach still bore the hallmarks of Soviet-era heavy industry. We couldn’t quite work out what if any method there was behind these renovations or the absence thereof. I suppose there was some logic behind it but I couldn’t fathom what it could be. An American colleague mentioned he’d visited Riga back in 1984 and was impressed by the architecture, so I wonder if earlier repairs had been undertaken.4 I mention this because both the Jewish Community in Latvia building/community centre and the KGB’s corner house we visited seemed more down at heel than others we saw. I am sure there are probably a range of probably quite mundane reasons for this situation but the differences stood out.

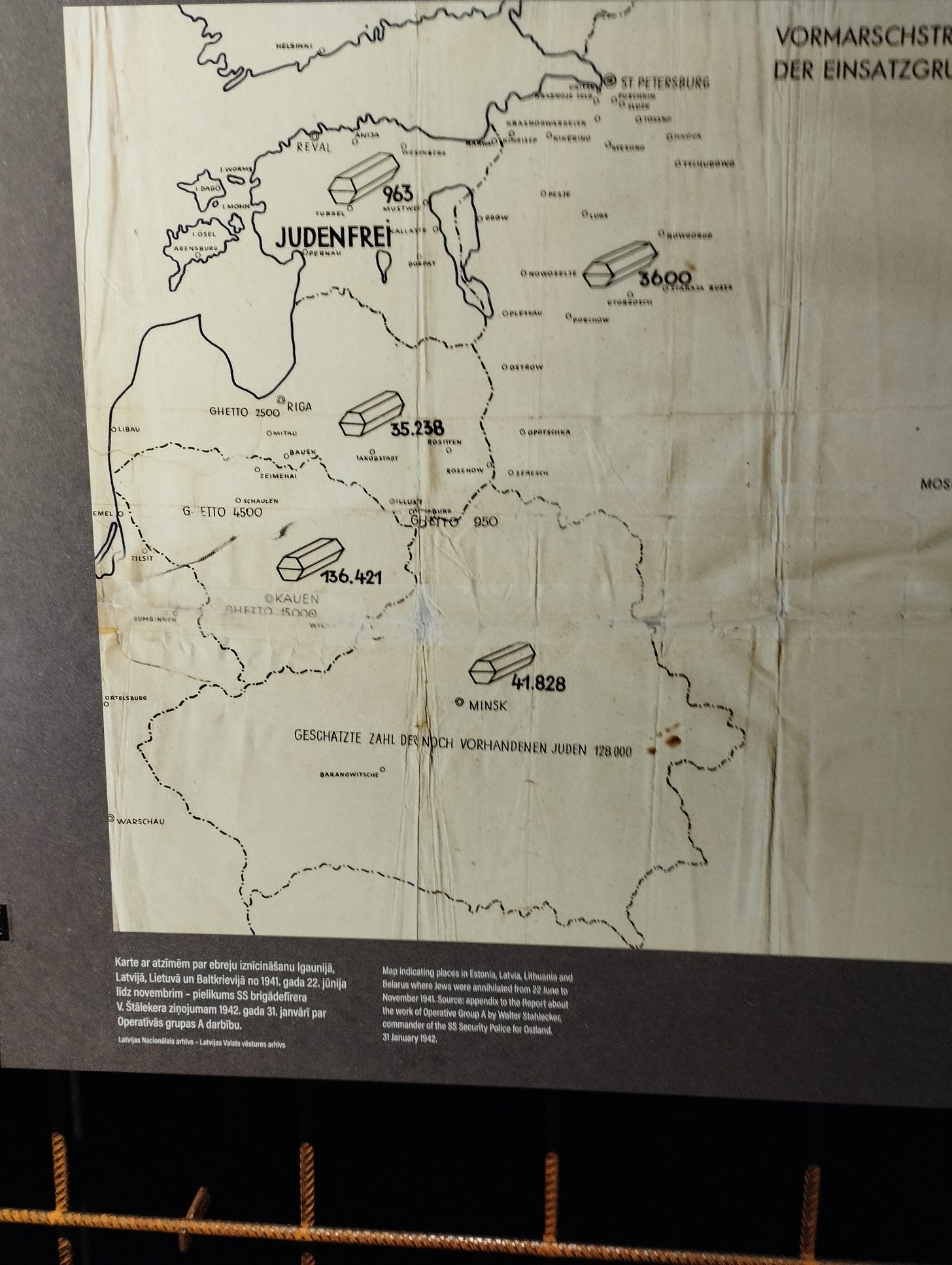

The KGB building’s lacklustre, late Soviet interior exuded a sense of menace but most of the actual block seemed empty. The Jewish Community Centre was housed in a similarly neglected building. Through an open door, I caught a glance at its internal theatre, with Hammer and Sickle still embossed on the balconies — I took a photo which I deleted because it was too blurry, and when I returned to snap another the door was locked. It also housed a small museum about the country’s Jewish population and its fate in the Holocaust. We didn’t visit the site of Riga’s Jewish Ghetto on this occasion.

German merchants, Lavtian Riflemen and anti-Soviet partisans

Why are these observations of any interest? Well, I suppose because of the comparison with the well-kept museums sited in Town Hall Square; the House of the Blackheads and the Museum of the Occupation.5 These two buildings sit behind the Soviet moment to the Latvian Rifleman, on the banks of the Daugava river. The juxtaposition of these three features raised some complex questions about the city’s past and how it’s memorialised. I’ll resist the temptation to rant about post-1989 memory politics or the rise of the cult of Totalitarianism but it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that there’s some little awkwardness here.

On one level it’s a simple story: the old Teutonic Bruderschaft der Schwarzhäupter (Brotherhood of Blackheads) were militarised merchants whose guilds were part of the Teutonic crusades and Hanseatic League, eventually evolved, by the 1720s, into the region’s landowning political class under the Russian Tsars. Unlike the situation further west in Central Europe there wasn’t much in the way of local, native aristocracy, after the early C15th.6

These German-speaking rulers of the region held sway until the First World War and teh establishment of Latvian independence. They had done their best to retard the political representation and national inclinations of the local Latvians and Estonians up until this point, these german speakers were then ‘evacuated’ back to Nazi Germany in 1939.7 The House of the Blackheads was a warehouse and later cultural centre — which is where Wagner comes in — but it was destroyed in 1941.

I say ‘destroyed’ because nowhere in the museum could we find any information about who demolished the building. Was it because of the crossfire, or actions by the invading Nazis, or by the ‘defending’ Soviets? There were plenty of explanations about how the Soviets destroyed the house’s foundations in preparation for the construction of a grand square celebrating the ‘Great Patriotic War’ but far less about its destruction. They’ve done a magnificent job rebuilding it but it seems strange that so much time and effort was put into restoring a ‘German’ symbol at the heart of Riga.

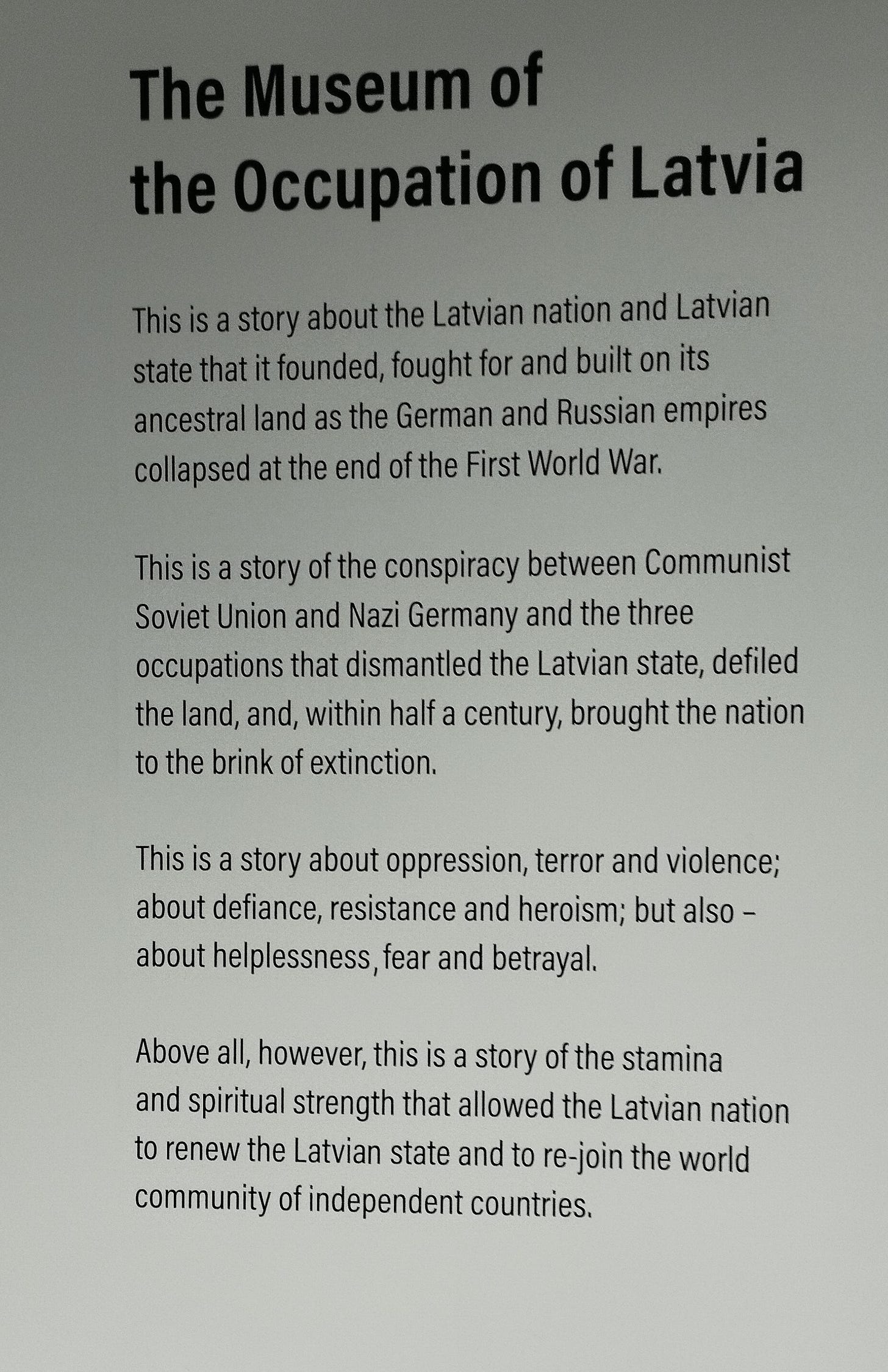

Adjacent are two objects commemorating the Red Latvian Riflemen. One is a massive statue of a duo of riflemen who fought alongside the Russian Empire against the Germans and then with the Bolsheviks, and, if memory serves, protected Lenin from assassination, behind them is their former museum (you can see it on the right in the photo above), now repurposed into the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia.8 It’s a strange combination and not one for me to comment on, but it neatly sums up the messiness of Latvian history at a glance.

Food and Latvian Calvados

I mentioned we were well-fed and watered in Riga. The beer and the Latvian snacks at Two More Beers were great. The food at Zivju Lete and Ferma was excellent. Plus we had no difficulties in getting fresh seafood in Riga, unlike some other littoral cities I could mention. But it was the side dish of Latvian potatoes, with chanterelles and cream at Tails which stood out for me. After dinner when I asked if they had any local specialities they offered us some Latvian Calvados,9 and I would go back for another round of those in a heartbeat.

Oh, and I’m just not going to mention forgetting my passport at the bus station and having to follow my partner 4 hours later on a different coach because that would just be embarrassing.

I make no apologies for being an unrepentant urban chauvinist. I don’t get the same feelings of city love from all Estonians in Tallinn who often seem keen to leave the city and get back into the countryside, waxing lyrical about its forests and bogs. I’d recommend a visit to Tallinn’s Open Museum to get a ‘feel’ for this impulse — it has a pub, so it’s not a complete waste of time. Nor, I hasten to add, is this urge unique to Estonians, many other Europeans are similarly afflicted.

I’ve struggled to find good (that is Baltic-centric, balanced), general Anglophone histories about Latvia, not that I’ve looked too hard, but I’d recommend Andres Kasekamp’s, A History of the Baltic States (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010) and Stephen Corrsin’s, ‘THE CHANGING COMPOSITION OF THE CITY OF RIGA, 1867-1913 Journal of Baltic Studies 13, no. 1 (1982): 19–39, the Journal is chock-a-block with fascinating articles so I’d recommend a look. Other books I consulted seemed far more interested in Western navies, and royal dynasties or simplistic anti-communism than with the local inhabitants themselves. Max Egremont’s, The Glass Wall: Lives on the Baltic Frontier (Pan Macmillan, 2021) seems useful, although I won’t pretend I’ve finished reading it yet.

It has been a complex, often fractious interaction between, German, Russian, and Latvian-speaking populations, I make no claims to have any deep insights to offer about these contacts and conflicts.

There’s often a persistent myth across CEE that no buildings were ever renovated during the Soviet/ socialist era, which is rarely true, as any visitor to Warsaw will know. There were often complex local reasons why some were rebuilt or not. Tallinn’s Tallinna Linnahall, constructed for the 1980 Moscow Olympics ( which starred in the movie Tenet ) is currently being left to rot, which is understandable but also a shame.

See the photos at the top of this posting

Martyn Rady, The Middle Kingdoms: A New History of Central Europe (Penguin Books Limited, 2023).

Their transfer back to the Reich was part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939, approx 50,000 left the country.

I posted the sign at the start of the museum’s exhibition space, and it contained much of what we expected. Take a look at Stephen M. Norris (ed.), Museums of Communism: New Memory Sites in Central and Eastern Europe (Indiana University Press, 2020).

Whether or not there’s any connection with Louis XVIII's exile in the Jelgava Palace I’ve no idea.